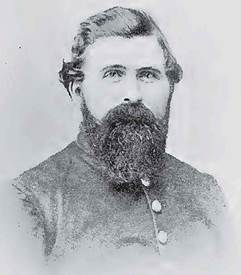

Links to stories about removing the Confederate Statue from the Courthouse Grounds:

Samuel C. Means, a Waterford Mill

Owner,

leader of the Loudoun Rangers

WHITE WASH

In

the past week, I urged that we remove the Confederate Soldier Statue, bearing a

rifle in the direction of approaching visitors to the court in Leesburg,

because it is an offending symbol of disunion, lawlessness and slavery.

In

2009, a Deputy Clerk at the Court, Jennifer Grant, reportedly told the Post

that she “didn’t like [the statue],” but “there were certain things people

didn’t talk about.”

Johnny

Chambers, on his way to Court this past Tuesday, told WUSA*9 that, “It’s hard

to get justice when you got people that live in this area, that run this

country, that believe in this system,”

pointing at the Confederate Soldier statue.

Leesburg

court personnel told me, “We all read what you wrote. We here talk among ourselves and some of us

have resented that statue. … You should

know you have support in this building.”

The

most virulent opposition to removing the statue claims that the statue’s not

about slavery, it’s just history.

Mr.

G. of Loudoun County said, “I hear people say that all the time – the Civil War

wasn’t really about slavery … get real, of course it was.” (Not all persons prefer to be identified

publicly; thus the initials.)

Ms.

R said, “I would contend that the Civil War was fought over States Rights to

use slavery as their economic engine.”

Mr.

S. said these confederate soldiers were “fighting to prop up the plantation

owners who both pumped them up on propaganda and forced them through

conscription to fight ..”

Mr.

W. said, “there was only one difference between the Confederate Constitution

and the U.S. Constitution, and it was the ‘right’ to own other human beings.”

In

our Constitution, we expressly state “we the people” seek “to form a more

perfect union;” the Confederate Constitution doesn’t say that – as it was born

of disunion.

Our

Constitution says we seek to “provide for the common defense;” the Confederate

Constitution said no such thing; in fact, the Confederates were breaching their

obligation to “the common defense” by seceding.

Our

preamble provides for the “general welfare,” the Confederate Constitution does

not.

As

for why the South seceded, Article I, Section 9, Clause 4 of the

Confederate States Constitution prohibited any law that denied or

impaired “the right of property in negro slaves …”

Article

IV, Section 2 of the Confederate States Constitution granted its

citizens the right to travel anywhere “with their slaves.”

Article

IV, Section 3, Clause 3 authorized slaves in any new confederate territory they

acquired, and presumably that included the North if the Confederates could win

the war.

So,

it was about slavery.

Otherwise,

the true history of Loudoun County has been white-washed.

Loudoun

Delegate John Janney presided over an extraordinary legislative session in Richmond,

convened by the Governor, on April 4, 1861.

Janney argued for union, and the delegates voted for Union, by a margin

of almost two to one, 89-45.

Rabid

secession leaders, however, sought to overturn the result. Intimidated union delegates left

Richmond. The second vote, on April 17,

supported secession, 88-55.

Some

called for a vote of the public. 50,000

rebel troops came into Virginia to “help.”

Union voters fled to Maryland.

Other Union voters were barred from voting. Some who did vote union were thrown into the

Potomac. There were disturbances at the

polls at Lovettsville and Lincoln. There

were directions to the troops that they could use bayonets at the polling

places. West Virginia withdrew from

Virginia on June 13, 1861, denouncing secession, and standing with the

union. When the remnant that was

Virginia counted the ballots, secession “won.”

Union

supporters were then arrested or driven out of Virginia. Confederate cavalry took teams of horses and

wagons from farmers in the German and Quaker settlements. If they didn’t have either, they were pressed

into service as drivers.

Samuel

C. Means owned the mill at Waterford.

He refused to take up arms against the United States. The Confederates took all of his property,

and his horses, wagons, hogs, flour, meal, everything. Means retreated to Maryland but returned

leading the Loudoun Rangers drawn from the Quaker and German settlements in

Loudoun to fight for the Union.

We

have no statue to the Rangers who remained faithful to the Union, only a plaque

opposite the Mill in Waterford.

In

the last week, we’ve also heard from those mobilized to oppose removal of the

statue, many of the same folk who unsuccessfully fought to place confederate

flags in Leesburg. Among the hard worded

opposition, there is only one e-mail correspondent that may fairly qualify as a

threat -- and we’re forwarding that one to the authorities.

It

is right and just to remove this statue.

Speak out if you agree.

TAKE THAT STATUE DOWN

Take

that confederate soldier statue down that stands in front of the historic

Leesburg Court House!

It’s

a symbol of disunion and slavery. If

it’s to stand anywhere, let it be in a museum but not at the front of a court

of law on public grounds.

Our

forebears could have placed a less offensive symbol in front of the court house

in 1908. But they didn’t. They intended to make a statement – an

unacceptable statement – and it’s high time we rejected that offensive

statement.

Years

ago, in the 1980s, there were stocks and whipping posts in front of this same

court house.

I

made reference at a sentencing in the court house once, how it was

“unfortunate” that such dehumanizing and tortuous methods of punishment stood

directly in front of a court house when we were considering punishment in a

criminal case.

According

to the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1839, a slave “was placed in a sitting

position, with his hands made fast above his head, and feet in the stocks, so

that he could not move any part of the body.”

This took less effort than whipping.

So, it became preferred as a punishment because, well, it took less

physical effort.

No

doubt others thought that these instruments of torture should be removed – and

they were.

Now

we should finish the job – and remove the statue as well.

The

Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution abolished “slavery” and

“involuntary servitude” and granted Congress the power to enact “appropriate

legislation.” By the 1866 Civil Rights Act, black citizens enjoyed “the full

and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for security of person and

property as is enjoyed by white citizens.”

Under

the Amendment and the 1866 Act, what were called “badges of slavery” were

outlawed.

Plainly,

stocks and a whipping post were “badges of slavery.” This statue is as well.

Since

1908, this confederate soldier has stood directly in front of the old

courthouse, elevated on a pedestal, with his rifle pointed straight at you as

you approach the old courthouse.

A

Confederate soldier plainly represents what he fought for, for disunion, so

that any state could ignore the constitution and break its constitutional

compact with every other state, violate the law of the land, in order to

preserve and spread slavery into the territories, to continue the stigma, the

badges of slavery, in perpetuity.

President

Andrew Jackson reprimanded Vice President John C. Calhoun at a party in 1830,

saying, “Our Union must be preserved.”

Calhoun

feared that, if slavery were abolished, whites would be forced into that

working class, at low pay. Calhoun

asserted the right of states to nullify what they didn’t want.

In

1858, Abraham Lincoln said in Springfield, Illinois that, “a house divided

against itself cannot stand.” He said

those who favored slavery were of the view, “if any one man, choose to enslave

another, no third man shall be allowed to object.” Lincoln said one object of the Scott decision

was to deny citizenship to slaves so they had no rights or privileges.

All

who approach this statue may rightly recall the unequal treatment before the

law suffered by persons of color and how it persists to this day long after the

civil war.

Many

know about the kidnapping and murder in 1955 of the black youth, Emmett Till, 14,

how the trial concluded with acquittals, followed by the admissions of the

acquitted defendants, bragging to a magazine, how they had really done the

dirty deed.

Medgar

Evers, an NAACP field secretary, was killed in 1963 because he sought to

overturn segregation in the South. When

Byron De La Beckwith, of the White Citizens Counsel, was tried, two all-white

juries deadlocked. In 1994, 30 years

later, De La Beckwith was tried and convicted.

The

NAACP came into existence about the time our Confederate Soldier was installed;

the Klu Klux Klan returned re-vitalized about the same time.

Virginia

was infamously known for its massive resistance against segregation. In Loudoun, we had segregated schools, movie

theaters, the pool; in fact, when directed to open the pool to black and white

alike, the pool was filled with cement.

It’s

therefore no metaphorical coincidence that we have this imposing bronze

soldier, the symbol of the southern nullification movement that set out to

disunite our nation, confronting every citizen who approaches our courts of

law.

It

is long past the time when we can pretend that a confederate soldier statue is

not itself a badge of slavery.

It’s

long past the time when we should take it down.